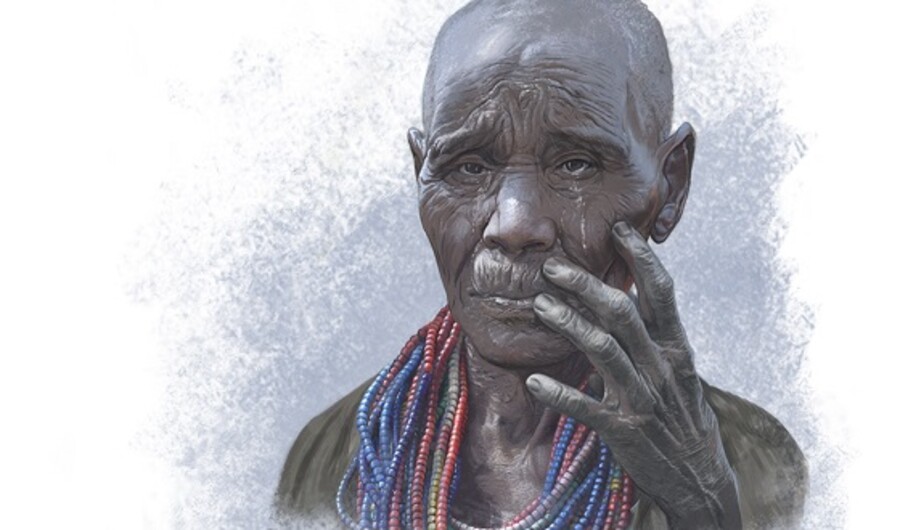

GARY DORNING/DETROMPET

The Selfish People

Imagine a society where no one gave and everyone sought only to get. What kind of a life would that be? Anthropologist Colin M. Turnbull experienced it firsthand.

Turnbull lived among the Ik tribe in northern Uganda from 1964 to 1967. He dedicated his 1972 book on the experience, The Mountain People, this way: “For the Ik, whom I learned not to hate ….”

What Turnbull witnessed in his time with the Ik stirred his emotions to hatred, finally fading to empty indifference. He experienced a society of about 2,000 members that had forgotten how to be human. They had lost the ability to love, hope and help. They had abandoned any semblance of living the give way.

In the Ik, Turnbull believed he saw the end result of what was happening in Western societies. He wrote that the Ik “had cultivated individualism to its apex.” Their only concern was working to fill their own stomachs and to keep everyone else’s empty. While they existed in a group in terms of proximity, each member lived in total emotional isolation. They lived a life of utter selfishness.

This example truly serves as a chilling warning to society today.

What Is ‘Good’?

As Turnbull observed the Ik’s culture, he sought to understand their motivations. He asked members of the tribe what their native word for “good” was. The word translated basically as “food.” And he learned that a “good man” was a man with food—in his own stomach. The younger Ik literally stole food out of the mouths of the elderly, waiting until they had chewed it. Young men hoarded excess food for themselves while their fathers died of starvation a few feet away.

Not much is known about the tribe, but apparently they had not always been this way. Most believe they were hunters and gatherers for many years but were forced to adopt a more agrarian lifestyle. At one time, it appears they held together in families, but eventually they abandoned this. Turnbull witnessed many disturbing examples of what happened when family structure is absent.

In one instance, he witnessed the Ik having to quickly move a village. The young left the old, stepping over them without concern. “[T]here was a sudden exodus from the village, distant shouts of laughter,” he wrote. “[I] went to see what the excitement was about. It was someone else whom I had never seen before, dead Lolim’s widow. She too had been abandoned and had tried to make her way down the mountainside. But she was totally blind and had tripped and rolled to the bottom … and there she lay on her back, her legs and arms thrashing feebly, while a little crowd standing on the edge above looked down at her and laughed at the spectacle.”

No one cared to help this old widow. Turnbull intervened, giving her food and medicine. He hoped the extra food would motivate her family to allow her into the new village.

“So we gave her more food and made her eat and drink all she could, put her stick in her hand and pointed her the way she wanted to be pointed, and suddenly she cried,” he wrote. “Thinking she was afraid or wanted us to go with her, I asked, and she said no; she was crying, she said, because all of a sudden we had reminded her that there had been a time when people had helped each other, when people had been kind and good.”

The Ik, in a matter of about two generations, had forgotten how to give, how to care, how to love.

They were in a vicious cycle. The Ik would kick their children out of their homes when they turned 3. The children would band together, not in friendship, but for survival. The leader of the pack, who was the oldest and largest child, could eventually be pushed off a cliff by one seeking to replace him. The spirit of competition was rampant.

After a childhood without being loved or cared for, the Ik children grew to adulthood and returned the favor by beating and starving the elderly. In Ik culture, children were not good for anything and neither were the elderly. The only value was in the strong, who could get for themselves.

In the case of the old widow trying to enter her new village, the Ik became angry at Turnbull for wasting food and medicine on her. In their thinking, the old die, so let them die and don’t squander time or resources on them.

A Mother’s Unlove

In most societies, one of the deepest bonds of love is between a mother and her newborn. But even this bond was completely severed in the Ik tribe.

In one numbing example, a woman was carrying her baby in a sling while she gathered food in the forest. Uninterested in the child’s well-being, she dropped the sling to the ground with her baby in it. While she wandered off to search for food, a leopard came and ate the child! The mother was delighted: She no longer had to be burdened with the child, and the leopard would be sleeping after its meal.

Later, the tribe found and killed the leopard. They ate it—and the baby inside of it. The mother felt she had won on two accounts: She no longer had to look after the baby, and she got a meal. This made perfect sense to perfectly selfish thinking.

In two of the years that Turnbull was with the Ik, they experienced a great drought, so food was scarce. It would be easy to assume that their despicable behavior was simply an effort to survive the famine. But what the Ik did with what they received speaks volumes about how their way of get became deeply ingrained in their thinking. Because even when they had plenty, they persisted in their selfish practices.

The government provided aid rations for the Ik during the drought years. The rations had to be collected from a central location and distributed to each tribe member. The younger members of the tribe who were the strongest went to collect the aid. Partway back to the village, they stopped and gorged themselves on the food, so much so that they vomited. They brought nothing back for the starving elderly and children in their village. After all, a “good man” was one with food in his own belly, even if it was more than the belly could hold.

In the third year that Turnbull returned to visit the Ik, the rains had come to Uganda. There was a bumper crop, and the fields overflowed with food. Yet in the midst of abundance the Ik continued to live as they were accustomed. They decided they could get more food with less effort from the government, so they left their crops to rot in the fields.

“There was so much food they could never eat it all,” Turnbull noted. “The main trouble was that there was too much, and although each person had all he could eat, he was still unwilling to see others eat what he could not. Certainly nobody thought of saving for any future day, let alone next year’s sowing.”

Seeing how the Ik had surrendered completely to their basest self-desires, Turnbull wondered about the sexual relationships within the Ik tribe. Here too he found complete selfishness.

“Lolim and others of the older people told me, for instance, of how in the old days adultery had rated equal to incest as a crime …. But when I mentioned [his daughter’s] flirtatious life to him and asked if he was not afraid for her, he laughed and said that the Ik had dropped all that kind of thing, now anyone could sleep with anyone …. [T]his was yet another indication of how completely family values had broken down.”

A Warning for Us

Turnbull wrote that the Ik had created a monstrous society that was a “passionless … feelingless association of individuals that would spread like a fungus, contaminating all it touched.”

In his conclusion, Turnbull made this startling statement: “[T]he symptoms of change in our society indicate that we are heading in precisely the same direction.”

Looking at daily headlines makes Turnbull’s warning eerily relevant. Consider recent news stories of parents abusing and selling their own children, leaving them in hot cars while they shop or do drugs, caging them in rooms while they party. One recent report told of three young women who worked at a nursing home; while an elderly patient behind them died of a stroke, they made a video of themselves smoking drugs and making lewd comments. They posted the video under the title “The End.”

How much is “advanced” Western society, having cast off moral restraint, losing its humanity and approaching the Ik way of life? As Ik society showed, the descent can happen alarmingly fast.

God foretold the characteristics of mankind just before the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. The list in 2 Timothy 3 reads like a character description of the Ik tribe that Turnbull witnessed: lovers of their own selves, covetous, disobedient to parents, unthankful, unholy, without natural affection, trucebreakers, false accusers, fierce, lovers of pleasures more than lovers of God.

Does not this abbreviated list also sound like a description of today’s American and British cultures?

Turnbull saw a spiritual truth, though he didn’t recognize it as such. “The Ik teach us that our much-vaunted human values are not inherent in humanity at all,” he wrote. This perfectly corroborates what is revealed in Jeremiah 17:9: The human heart is not inherently good; it is “deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked.”

The Ik are an example of what the get way of life looks like in full bloom—or, rather, total rot. Their history illustrates what the world would be like without giving—and it is the worst kind of horror show!

What made Colin Turnbull so disillusioned after his time with the Ik was the realization of how evil man can become. But he didn’t know the solution to the problem.

The Solution

God’s Word gives the solution.

Acts 20:35 records that Christ said it is more blessed to give than to receive. God created family so we can practice the give way in our own homes. God’s law shows us how to give. It is a “law of liberty” (James 1:25; 2:12), one that frees us from the terrible prison of the get way of life. God’s law commands that children love and honor their parents and that parents love, provide for and teach their children. All are taught to honor the elderly, and the elderly are to instruct the young.

The beauty of God’s plan is that it includes every person who has ever lived, including the Ik. Through a resurrection, even they will have the opportunity to learn God’s way of give.

As we look back on the Ik culture and see our modern societies becoming more selfish, we should be all the more motivated to live God’s give way and diligently teach it to our own children. ▪